PSYCHOLOGICAL MECHANISMS BEHIND THE ACCEPTANCE OF DEEPFAKE-BASED HUMOR AND DIGITAL HARASSMENT

DOI:

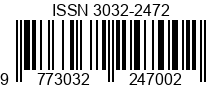

https://doi.org/10.62567/micjo.v2i4.2093Keywords:

Deepfake, oral disengagement, online disinhibition, digital harassmentAbstract

The objective of this study was to examine how deepfake-based humor becomes socially acceptable despite its potential to function as digital harassment. This study focused on psychological mechanisms that explain audience tolerance and normalization of harmful, identity-based humorous content in online environments. This study used a scoping review design to map and synthesize existing research across psychology, media studies, and cyberpsychology. The sources were identified through searches in major academic databases and were selected based on their relevance to deepfake technology, digital humor, online harassment, and psychological processes such as moral disengagement, online disinhibition, empathy reduction, and social norm reinforcement. The results indicate that acceptance of deepfake-based humor is commonly supported by four interrelated mechanisms, namely normalization through participatory digital culture, psychological distancing that weakens empathy, moral ambiguity created by humorous framing, and reduced accountability through diffusion of responsibility in online spaces. In addition, the literature conceptualizes deepfake humor as a hybrid phenomenon situated between remix-based entertainment and identity-targeting harm, shaped by platform visibility and engagement dynamics. This review highlights that deepfake-based humor may be tolerated not because it is harmless, but because it is routinely framed as “just a joke,” making its harm easier to minimize and socially overlook. Therefore, this study emphasizes the need for more direct empirical research and stronger interventions to prevent deepfake-based humor from becoming a normalized form of digital harassment in increasingly synthetic digital environments.

Downloads

References

Ahn, S. J. (Grace), Bailenson, J. N., & Park, D. (2014). Short- and long-term effects of embodied experiences in immersive virtual environments on environmental locus of control and behavior. Computers in Human Behavior, 39, 235–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.07.025

Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(3), 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0303_3

Bandura, A. (2016). Moral disengagement: How people do harm and live with themselves. Worth Publishers.

Billig, M. (2001). Humour and hatred: The racist jokes of the Ku Klux Klan. Discourse & Society, 12(3), 267–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926501012003001

Bourdieu, P. (2001). Masculine domination. Polity Press.

Bucher, T. (2018). If...Then: Algorithmic power and politics. Oxford University PressNew York. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190493028.001.0001

Citron, D. K., & Chesney, R. (2019, February). Deepfakes and the new disinformation war. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2018-12-11/deepfakes-and-new-disinformation-war

Dynel, M. (2016). “I has seen Image Macros!” Advice animals memes as visual-verbal jokes. International Journal of Communication, 10, 660–688.

Fiesler, C., & Proferes, N. (2018). “Participant” Perceptions of Twitter Research Ethics. Social Media + Society, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118763366

Ford, T. E., Boxer, C. F., Armstrong, J., & Edel, J. R. (2008). More than “just a joke”: The prejudice-releasing function of sexist humor. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(2), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167207310022

Im, J., Schoenebeck, S., Iriarte, M., Grill, G., Wilkinson, D., Batool, A., Alharbi, R., Funwie, A., Gankhuu, T., Gilbert, E., & Naseem, M. (2022). Women’s perspectives on harm and justice after online harassment. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 6(CSCW2), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1145/3555775

Jane, E. (2017). Misogyny online: A short (and brutish) history. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473916029

Kira, B. (2024). When non-consensual intimate deepfakes go viral: The insufficiency of the UK Online Safety Act. Computer Law & Security Review, 54, 106024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2024.106024

LaCroix, J. M., & Pratto, F. (2015). Instrumentality and the denial of personhood: The social psychology of objectifying others. Revue Internationale de Psychologie Sociale, 28(1), 183–212.

Matamoros-Fernández, A. (2017). Platformed racism: the mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 20(6), 930–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1293130

Matamoros-Fernández, A., Bartolo, L., & Troynar, L. (2023). Humour as an online safety issue: Exploring solutions to help platforms better address this form of expression. Internet Policy Review, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.14763/2023.1.1677

McGraw, A. P., & Warren, C. (2010). Benign Violations. Psychological Science, 21(8), 1141–1149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610376073

Meyer, J. C. (2000). Humor as a double-edged sword: Four functions of humor in communication. Communication Theory, 10(3), 310–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2000.tb00194.x

Milner, R. M. (2016). The World Made Meme. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262034999.001.0001

Paris, B. (2021). Configuring fakes: Digitized bodies, the politics of evidence, and agency. Social Media + Society, 7(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211062919

Phillips, W., & Milner, R. M. (2021). You are here. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/12436.001.0001

Reicher, S. D., Spears, R., & Postmes, T. (1995). A social identity model of deindividuation phenomena. European Review of Social Psychology, 6(1), 161–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779443000049

Romero-Moreno, F. (2024). Generative AI and deepfakes: a human rights approach to tackling harmful content. International Review of Law, Computers & Technology, 38(3), 297–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600869.2024.2324540

Shifman, L. (2014). Memes in digital culture. The MIT Press.

Suler, J. (2004). The online disinhibition effect. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 7(3), 321–326. https://doi.org/10.1089/1094931041291295

Udris, R. (2014). Cyberbullying among high school students in Japan: Development and validation of the Online Disinhibition Scale. Computers in Human Behavior, 41, 253–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.09.036

Vaccari, C., & Chadwick, A. (2020). Deepfakes and disinformation: Exploring the impact of synthetic political video on deception, uncertainty, and trust in news. Social Media + Society, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120903408

Weller, K., & Kinder-Kurlanda, K. E. (2016). A manifesto for data sharing in social media research. Proceedings of the 8th ACM Conference on Web Science, 166–172. https://doi.org/10.1145/2908131.2908172

Woodzicka, J. A., Mallett, R. K., Hendricks, S., & Pruitt, A. V. (2015). It’s just a (sexist) joke: Comparing reactions to sexist versus racist communications. HUMOR, 28(2). https://doi.org/10.1515/humor-2015-0025

You, L., & Lee, Y.-H. (2019). The bystander effect in cyberbullying on social network sites: Anonymity, group size, and intervention intentions. Telematics and Informatics, 45, 101284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2019.101284

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2026 Kurrota Aini, Vidya Nindhita, Hapsari Puspita Rini

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.